[ Homepage ] [ Introduction ] [ Warning ] [ Ratings ] [ Ethics ] [ Feedback ] [ Updates ]

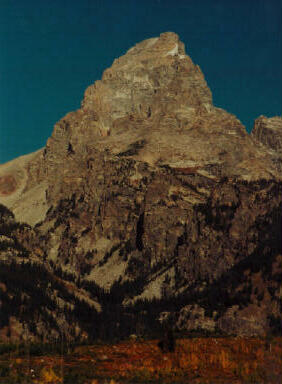

I started to think of all the time and energy which has gone into planning and training for this climb. The idea of climbing the Grand Teton began, almost one year before, while rafting the Snake River near Jackson Hole, Wyoming. I could see the 13,770 foot summit of Grand Teton in the distance, towering over everything in sight. This perfectly proportioned looking mountain, considered one of the world's classic climbs, seemed like a worthy enterprise for a 39-year-old weekend adventurer. The Teton Range is an infant geologically. At only nine million years old, this 40 mile-long, 15 mile-wide formation is still growing. During the last two million years, its eastern edge has risen an average of five inches per century. Currently, the Grand Teton towers 7000 feet above the town of Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Nathaniel Langford and James Stevenson allegedly first climbed the Grand Teton on July 22, 1872. As is typical of many famous mountains, there is a significant controversy over whether Langford and Stevenson actually reached the summit. The first verifiable assent belongs to the Owen-Spalding party, which on August 11, 1898 summited four climbers. I figured this adventure would be much more fun with a companion. I recruited my 37-year-old brother, Todd Burrows. After I told him the climb would be a physical torture test, Todd was an easy recruit. Todd would consider the Battan Death March an amusing tramp in the woods. Next on my list of recruits was 37-year-old, life long friend, Greg Frei. Greg is always ready for an exciting backcountry adventure. Greg is intensely happy when the nearest road is an 8-hour hike away. The last member of the gang was 42-year-old Milo White. The Grand Teton was mentioned in a casual conversation, and I was surprised to hear that Milo had already contemplated climbing Grand Teton and was looking for someone else to attempt the climb with him. I was also astonished to discover that Milo was winning a battle with thyroid cancer. The first problem that we encountered was that none of us had ever done any serious rock climbing. This proved to be a comparatively minor obstacle once we hired Exum Utah Mountain Adventures to teach us what we would need to know. This training in technical rock climbing was completed over a packed spring weekend. Todd, Milo and I completed a climb up the spectacular North Face of Salt Lake City's 9026 foot Mount Olympus. The Mount Olympus climb was very demanding since it contained a mix of rock and ice. The approach route includes a very steep, one-mile long snow and ice filled chute, requiring the use of an ice axe and crampons, which are metal spikes strapped to the bottom of your boots. This leads to the base of a massive 2200 foot crag where the rock climbing begins. Technically, this climb was much more than would be required on Grand Teton.

The physical training was not achieved as easy as the technical training. My physical training consisted of running or mountain biking one or two hours every weekday evening for one year. If the weather did not cooperate, the evening was spent on a stair climber. Weekends were spent climbing 11,000 foot Wasatch Front Mountains, in summer and winter. One side benefit was that I entered several mountain bike races to help relieve the boredom of training and actually won some money. The 30 to 39 year old, beginners, mountain bike class is not seriously contested. Most of the racers are like myself and just out for an enjoyable evening ride. The next problem was that we did not know where we were going or how to get there. Hiring Jennifer and Cody from Jackson Hole Mountain Guides (JHMG) to show us the route and to stop us from committing mountaineering suicide solved this. I really felt better about hiring JHMG after three climbers were helicoptered by Life Flight from the Grand Teton the day of our arrival in Jackson Hole. The three climbers were injured in two separate lightning strike accidents. Lightning is an extreme danger when climbing in Grand Teton National Park, since the mountain range is struck with a transient thunderstorm almost every afternoon. The added benefit of hiring JHMG was that tents, sleeping bags and climbing gear were provide for us at high camp. This makes the hike to high camp more enjoyable, particularly since high camp is located approximately 8 miles and 4300 feet above the trailhead at Lupine Meadows. At 11,000 feet, and with commanding views of Garnet Canyon and the Middle Teton, JHMG high camp is situated amidst boulders and beneath soaring granite spires. I thought about lying in my warm sleeping bag early last evening, with the breeze rattling the broken zipper on the tent flap. I overheard the guides in the adjacent dining tent talk about how many of their clients actually summited Grand Teton. The guides take great pride in their success ratios and use it as a measure of their abilities. I heard Jennifer say our group was her 5th group of the year. Two of the four groups before us have put climbers on the summit. This is about the standard success rate for clients among the other guides, with physical conditioning and weather being the typical cause of defeat. This is Cody's first time guiding in the Teton's this year. He has been guiding clients on Devil's Tower in northeast Wyoming. I also take time to contemplate the gourmet meal we had for dinner last evening. Understand that we had just spent 5 hours climbing to high camp, through all types of weather, from blazing hot sun to a marble size hailstorm. We were very hungry. The JHMG gourmet meal was made in the following manner. Your bowl was retrieved from the backpack and cleaned with your shirtsleeve. Uncooked angel hair spaghetti noodles are placed in the bowl. Warm water is poured over the noodles and allowed to stand for one minute. The water is then drained from the bowl and something that was referred to, as red sauce, but I believe was ketchup, is poured over the noodles. I wonder if this nauseous feeling I have is from the altitude or from last night's dinner? After climbing through a moraine, which is a battleground of gravel, rocks and boulders deposited by glacial movement, we encounter our first real challenge just below the Lower Saddle. My daydream ends when confronted with a 100-foot stretch of technical scrambling up exposed and possibly dangerous rock and ice. This barrier has a climbing aid in the form of a thick braided rope, which has been placed by the park service. This is the last obstacle before invasion of the Lower Saddle at 11,650 feet, which is formed where Middle Teton meets Grand Teton. I am certain that the Lower Saddle is the most wretched piece of terrain in the entire Teton mountain range. The Lower Saddle is always cold, wind blown and sparsely populated by tents belonging to mountain climbers. There are no trees or bushes at the Lower Saddle since we are several thousand feet above timberline. Middle Teton Glacier occupies a portion of the Lower Saddle and is the last reliable water source before the summit. The Lower Saddle has one interesting attraction, which is visited by many climbers. There is an actual chemical toilet with an extraordinary view. Understand that this toilet, which faces the setting sun, has only a 3-foot wall surrounding the commode. You can have a seat and see the entire state of Idaho. We fill our water bottles from glacial melt and leave the Lower Saddle. We continue the grind by climbing through a labyrinth involving some scrambling and technical climbing towards the Upper Saddle at 13,000 feet. Our lungs are fighting to extract every drop of oxygen from the thin air to power our abused leg and arm muscles. Some of us are suffering nausea from the altitude. Since retreat is not a preference, the only remedy for nausea is to force down water and food. We are moving fast and strong as we overtake two climbing groups that started before us. This maze between the Lower and Upper Saddle is where I am happy to have Jennifer and Cody from JHMG leading the way. It would be easy to climb into a difficult situation in the unfamiliar terrain in the early morning darkness. It is at this point that my headlamp quits working. Never trust a headlamp you purchased for $3.95 at Wal-Mart. Fortunately, it is now almost light enough to see. If I stick close to the climber in front of me, I can place my feet in his vacated steps. Playing follow the leader has one major advantage. I find a climbing rhythm. Our guides will not allow us to stop and rest. It would be so easy to just sit down and quit, but the disappointment of failure would be worse than the suffering caused by continuing the climb. Looking back down the route, I see a steady snake of headlamps stretching down past the glacier we left hours earlier. It appears we are not the only summit hopefuls today. Standing in the bitter cold, looking up at several hours of hard climbing ahead, I have a hard time remembering why I chose to do this for my summer vacation. I could be sitting on a sunny beach drinking margaritas, but such a vacation always leaves me feeling incomplete and empty.

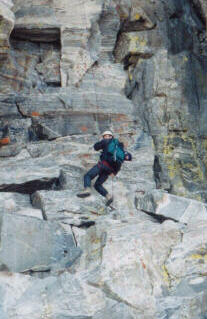

We arrive at the 13,000 foot Upper Saddle moments before sunrise and are greeted with a very amazing sight. The shadow of Grand Teton is being projected over the entire state of Idaho. I wonder if the climber occupying the commode in the Lower Saddle is appreciating this view? At the Upper Saddle, we are hit with the full force of the wind. I notice immediately that we will not have to worry about our climbing ropes becoming snagged, since the wind is picking the ropes up from the ground and forcing them to form a large skyward arc between climbers. It is at this point that the real climbing begins. We divide into two rope teams. Jennifer, Greg and Milo form the first team. Cody, Todd and I form the second team. The Pownall-Gilkey route, first climbed in August 1948, traverses right, or south, along a narrowing ledge system. The first pitch is rated 5.8 and is the crux of the route. When climbing ratings were first established, technical climbs were noted with the number 5, and rated easiest to hardest with the numbering system 5.1 to 5.9. It is at this point that I learn 5.8 in the valley on a warm summer day in shorts and climbing shoes is totally different than 5.8 at 13,000 feet, at sunrise after climbing most of the night, in hiking boots, with below freezing temperature, and gale force winds. One more item to spice up the climb was that many of the rocks above the Upper Saddle were covered with a fine ice coating called "verglas", which eliminated a large number of holds and forced us to step with discretion. This is also the point in the climb where Todd and I were forced to sit on a narrow ledge and shiver in the frigid weather for over an hour, while we waited for two teams of climbers to clear the first pitch ahead of us. Our guide Cody had gone ahead to belay (safeguard with a rope) other climbers in order to help clear the route. There was nothing left for us to do but talk about how cold we were and shiver. I would have added more clothes, but I don't know how I could have put them on. I was already wearing polypropylene underwear, a fleece vest, a fleece jacket, wool hat, wool gloves and a weatherproof Gore-Tex shell. Above the crux, I had been told the climbing eases to a rating of 5.6. However, I don't think this rating takes into account the rock being coated with ice 1/2" thick. This next obstacle is a 30-foot friction pitch, which you could easily walk up if it were warm and dry, but it is covered with a solid ice sheet. I knew it could be climbed because Cody had already led the pitch over this section. He was belaying me from a hidden alcove above. I could not ask Cody for direction because the wind ripped the words from your lips and scattered them in every direction. I knew that Todd was still below, sitting on the ledge, nauseous from altitude, and freezing from inactivity. I needed to climb as fast as possible. I decided that if Cody could climb this section, then it should not stop me. I conveniently forgot that Cody was a professional mountain climber and I was a weekend warrior climbing my first big mountain. Studying the problem again, I noticed a small strip of dry rock near the edge of the friction pitch and decided this was my ticket, if it ran all of the way to the top. I started up the pitch until I was jerked hard backwards. I could not turn to see what was grabbing and holding me because of my backpack, hat, helmet and all of the clothes that I was wearing. All this gear made it very difficult to look any place but forward. I downclimbed several feet and noticed that I had forgotten to unclip my rope and move it around the protection that the lead climber had placed in the rock. With my rope corrected, I found that the path I had selected up the friction pitch was a good one and led to a small chimney.

My arms and legs were throbbing, and I again cursed my backpack as it caught on the rock at my back as I ascended the chimney. At the top of the chimney, I joined Cody at the belay stance and began coiling rope for our next pitch. It felt good that I was off the pitch, because I knew Todd was cold and miserable below. Climbing would warm him fast and take his mind off any altitude sickness. From here, we traversed exposed rock and ice requiring scrambling and technical climbing over risky terrain, until the route broke into the warming sunlight on Exum Ridge. We scrambled up Exum Ridge, with its tremendous exposure on both sides as we headed for the summit. We were moving as one unit, still tied into our climbing ropes. This is known in mountaineering as "walking in coils". Walking in coils is an extremely fast way of traveling, since all of the climbers are moving at one time. However, if one climber were to fall, he could easily drag the rest of the team over the edge. Speed and safety are always a compromise in climbing the Teton's, since your safety lies in your speed to ascend to the summit and then descend to a sheltered area before the afternoon thunderstorms attack the peaks with viscous lightning bolts. At 10:30 a.m. we reached the summit and were greeted by the first rope team. We looked upon a cloudless sky, a warming sun, a stunning 360-degree view and the relentless wind. On the highest point for miles, we enjoyed a moment of rest, a sandwich for an early lunch, and a feeling of great accomplishment. We snapped some pictures before leaving this extraordinary place, to show we had stood on the roof of the Teton's. It was very hard to leave the summit, but our climbing day is only half over. As the first rope team began the steep down climb from the summit, our guide Cody proves his value again. He led Todd and I to a little known rappel, which eliminates this ponderous down climb. The first rope team was envious, and hurled good-natured insults in our direction as we whizzed past them on our rappel lines. From the bottom of our first rappel, we walked a ledge to the top of the traditional long summit rappel. This famous rappel deposits the climber on the Upper Saddle from an overhanging ledge. The climber is suspended in space, more than 100-feet above the rock of the Upper Saddle. This is known as a "free rappel" and is extremely exciting. Considering the wind was blowing the climber like a pendulum, exciting is probably an understatement. I enjoyed watching Todd on the traditional rappel, since it was his first free rappel and only his third rappel ever. I have never seen eyes that big before. We began the downclimb to the Lower Saddle. After descending several hundred feet, we are in jeopardy when climbers above us unwittingly start a rockslide. We all hug the rock wall like a long lost love as large rocks crash over our heads. This incident is terrifying for everyone below the rockslide. The feeling of helplessness as rocks tumble from above us is unbelievable. Our guides use the technical mountaineering term "dumb ass" as they shout to the climber who started the rockslide. We continue downclimbing towards the Lower Saddle. Having ascended by headlamp, it would have been easy to choose the wrong gully on the descent, but Jennifer and Cody lead us back through the maze to the Lower Saddle. We stopped briefly to shed excessive clothing, enjoy a long drink from the water purring off Middle Teton glacier in the midday sun, and refill water bottles, which have been empty for hours. As we continued down, I am astonished at what the human body can accomplish when pushed to its limits. The hike out was, of course, anticlimactic. We would not reach the trailhead until 6:00 p.m. after continually climbing for 15 hours. In two days, I would be back at work, in a climate-controlled office, staring at a computer screen and this would all seem like an illusion. [ Homepage ] [ Introduction ] [ Warning ] [ Ratings ] [ Ethics ] [ Feedback ] [ Updates ] © Copyright 1999, Shane Burrows |