[ Homepage ] [ Introduction ] [ Warning ] [ Ratings ] [ Ethics ] [ Feedback ] [ Updates ]

April 26, 2003, started as a routine Saturday of climbing for Aron Ralston, an avid outdoorsman and mountain climber. He planned to spend the day riding his mountain bike and climbing the red rocks and sandstone just outside the Canyonlands National Park in southeastern Utah. The area is some of the most desolate and intriguing wilderness in the lower 48 states with areas of buttes, mesas and convoluted canyons. Ralston had climbed alone before plenty of times. He had scaled all 59 of Colorado's 14,000-foot peaks, 45 of them solo in winter, and this outing was a warm-up for an ascent of North America's highest mountain, 20,320-foot tall Mount McKinley. Ralston, 27, of Aspen, Colorado, parked his pickup truck at the Horseshoe Canyon Trailhead and took off on his mountain bike for the 15-mile ride to the Bluejohn Canyon Trailhead where he locked his mountain bike to a juniper tree. Dressed in a T-shirt and shorts and carrying a backpack he planned to canyoneer down remote Bluejohn Canyon and hike out adjacent Horseshoe Canyon to where he parked his truck and then go back for the mountain bike. His backpack contained two burritos, less than a liter of water, a cheap imitation of a Leatherman brand multi-tool, a small first aid kit, a video camera, a digital camera and rock climbing gear. The backpack did not contain a jacket or extra clothing. Canyoneering is where a climber uses rock-climbing skills, ropes and gear to negotiate narrow slot canyons.

Within the first hour after becoming trapped Ralston had calculated his options and came up with four possible solutions.

Death was a 5th possibility that Ralston didn't want to consider. Ralston tried ropes, anchors, anything to move the boulder, but it wouldn't budge. Next he tried to chip away at the rock with a cheap imitation of a Leatherman brand multi-tool, with no positive results. Ten hours of chipping at the rock managed to produce only a small handful of rock dust. Temperatures dipped into the 30's at night, and still Ralston worked to free himself. Sunday and Monday passed but he was still trapped. Sunlight reached the narrow canyon floor for only a very short period of time each day. He ran out of food and water on Tuesday. On Wednesday, Ralston began sipping the urine he had started saving a day earlier. He pulled out his video camera and recorded a message to his parents. He next etched his name, birth date, and what he was certain was his last day on earth into the canyon wall. He topped it off with RIP. On Thursday morning, Ralston had a vision of a 3-year-old boy running across a sunlit floor to be scooped up by a one-armed man. He understood this vision to be of his future son and decided that his survival required drastic action. If he did not rescue himself now, he would not have the physical strength remaining to do it later.

Ralston prepared to amputate his right arm below the elbow using the knife blade on his multi-tool. Realizing that the blade was not sharp enough to cut through the bone he forced his arm against the boulder and broke the bones so he would be able to cut through the tissue. First he broke the radius bone, which connects the elbow to the thumb. Within a few minutes he cracked the ulna, the bone on the outside of the forearm. Next he applied a tourniquet to his arm. He than used his knife blade to amputate his right arm below the elbow. The entire procedure required approximately one hour.

The Dutch couple Eric and Monique Meijer and their son, Andy, had just finished photographing the famous Grand Gallery. As they packed up their gear and began to hike out of the canyon they heard a voice behind them cry "Help, I need help". The couple immediately realized that this must be the lost hiker whom they had been briefed about by a ranger earlier in the day. Ralston walked quickly toward

the couple. His arm, or what was left, hung in a self-made sling and he spoke clearly:

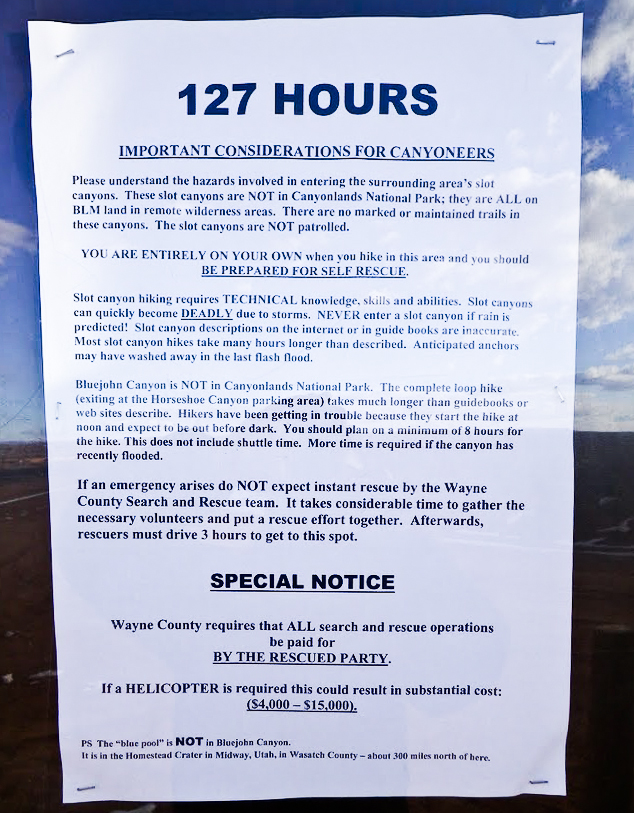

"Hello, my name is Aron, I fell off a cliff on Saturday and I was stuck under a

boulder. I just cut off my hand four hours ago and I need medical attention. I need a

helicopter". In the meantime Ralston’s friends at the Ute Mountaineer store in Aspen began to worry when he failed to appear for work and called authorities. The dilemma was that Ralston had neglected to notify anyone of his itinerary. His mother found out her son was missing Wednesday when his boss called her. A friend helped her break into her son's e-mail for clues on his whereabouts to no avail. Authorities in Aspen discovered he had used a credit card to buy groceries in Moab, Utah and notified authorities there to start searching for him. Mitch Vetere, a patrol sergeant with the Emery County Sheriff's Office in Green River, got the call Thursday morning. A climber was several days overdue. His truck had been found at the Horseshoe Canyon Trailhead, but no one had seen Ralston. Terry Mercer, a helicopter pilot with the Utah Highway Patrol in Salt Lake City, met Vetere and another deputy about 1:00 p.m. Thursday at Horseshoe Canyon, where Ralston's truck was parked. After reading notes and looking at Ralston's equipment in his truck, Mercer and Vetere knew Ralston was an experienced climber. The search helicopter was soon airborne and Mercer flew for about two hours - Nothing. Suddenly the flight crew noticed two people deep in Horseshoe Canyon waving. It was the Dutch wife and son and they were franticly signaling the helicopter and pointing in the direction of the victim. The flight crew quickly perceived the signals and landed in a wide spot in the canyon near Ralston. The flight crew was shocked at the sight - dry and fresh blood coating his body - and the missing arm. The rescue crew could not believe it; Ralston was within a mile of his pickup truck. He almost didn't even need to be rescued. After Ralston was helped into the helicopter, Mercer peeked back at him. Ralston's right arm was in a makeshift sling made from a Camelback used to carry water. Ralston leaned his head back in the helicopter and sipped on some water. Vetere kept him talking, so he wouldn't lose consciousness. Twelve minutes later, the helicopter arrived at Allen Memorial Hospital in Moab, Utah. Ralston walked into the emergency room without help, then pointed out on a map where he had been stuck. The rescuers were amazed at Ralston's will to live. A helicopter likely would not have found him because of his position in the deep and narrow slot canyon. Mercer and two other deputies went back into the canyon hoping they could retrieve Ralston's arm and that it could be reattached but the trip was futile. The deputies could not move the boulder. It would take thirteen men with equipment to later remove the severed arm. Aron Ralston had an amazing will to live, he never gave up and he saved himself. 127 Hours: Everything needed to visit the spot where Aron Ralston was trapped is included in my Bluejohn Canyon Route Information. Bluejohn Canyon is located in one of the most remote regions of the lower 48 states. The canyon is 40 miles from the nearest paved road and about 3 hours from the nearest town. If you are injured in this area mediocre medical care is at least 6 hours away. Bluejohn Canyon is

an extensive canyon system that requires 3 or 4 days to completely explore.

If you were doing the complete "Ralston Route" it would require a very long

day and one mandatory 70-foot rappel. If you wanted to visit the spot where

Aron's accident occurred you can hike down to it and back up without a

rappel. Doing that would require some scrambling and most of a day.

KUER Radio Interview:

Related Links:

[ Homepage ] [ Introduction ] [ Warning ] [ Ratings ] [ Ethics ] [ Feedback ] [ Updates ] © Copyright 2000-, Climb-Utah.com |

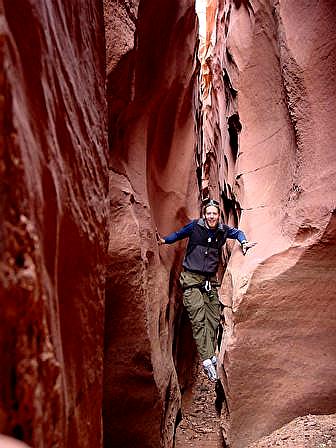

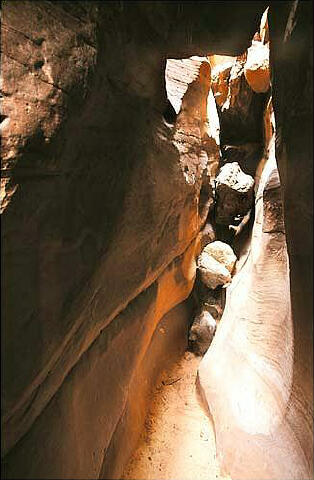

Ralston was

150 yards above the final rappel in Bluejohn Canyon. He was maneuvering in a 3-foot wide

slot trying to get over the top of a large boulder wedged between the narrow canyon walls.

He climbed up the boulder face and it seemed very stable as he stood on top. As he began

to climb down the opposite side the perfectly balanced 800-pound rock shifted several

feet, pinning his right arm - he was trapped.

Ralston was

150 yards above the final rappel in Bluejohn Canyon. He was maneuvering in a 3-foot wide

slot trying to get over the top of a large boulder wedged between the narrow canyon walls.

He climbed up the boulder face and it seemed very stable as he stood on top. As he began

to climb down the opposite side the perfectly balanced 800-pound rock shifted several

feet, pinning his right arm - he was trapped.

Ralston administered first aid to himself from the small kit in his backpack. He rigged

anchors and fixed a rope to rappel nearly 70-feet to the bottom of Bluejohn Canyon.

Leaving his rope hanging he hiked 5 miles downstream into adjacent Horseshoe Canyon, where

he encountered a Dutch family on vacation.

Ralston administered first aid to himself from the small kit in his backpack. He rigged

anchors and fixed a rope to rappel nearly 70-feet to the bottom of Bluejohn Canyon.

Leaving his rope hanging he hiked 5 miles downstream into adjacent Horseshoe Canyon, where

he encountered a Dutch family on vacation.