[ Homepage

] [ Introduction ] [ Warning ] [ Ratings

] [ Ethics ] [ Feedback ] [ Updates

]

|

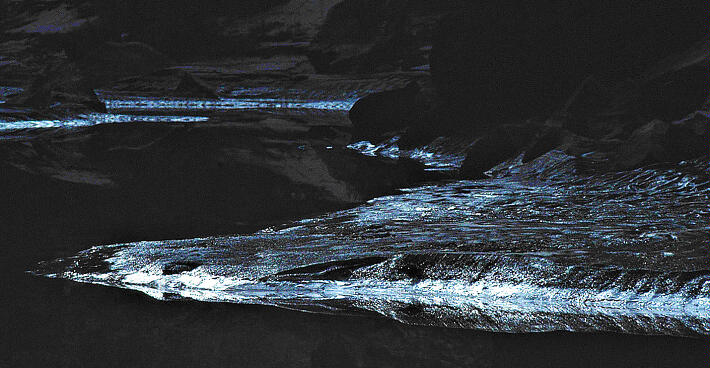

Little Colorado River

Gorge

January 1980

Rex Welshon

In

January, 1980, Charlie L, Gary W, Ron W, Frank V, John B, and I hiked

from Cameron, Arizona, to Grand Canyon National Park by descending the

Little Colorado River Gorge, traversing the Beamer Trail, and ascending

the Tanner Trail to Lipan Point. The trip took us fifteen days from

start to finish, four more than we expected. Along the way, we crossed

the Little Colorado almost a hundred times and encountered deep

quicksand. Gary partially tore his ACL on the fifth day and completed

the trip using a jerry-rigged splint and crutch. During the last three

days we were in the Little Colorado River Gorge itself, the river

flooded and stayed above flood stage almost until we got to the Beamer

cabin at the confluence with the Colorado.

It's been a long time

since this adventure, and the six of us are now a long way from being

who we were then. Nevertheless, many of my memories from this trip

remain utterly vivid. No individual part was as frightening as, say, a

long free rappel off a single bolt, and no single day was as

individually memorable as a couple of others I've spent in the boonies.

But the way the various aspects and components added up together have

made this trip indelible. A while back, I had the idea of gathering my

remaining thoughts about it. It's taken a while.

|

Day 1:

Arriving at Grand Canyon National Park at around 10 am, we

inform the ranger at the permit desk what we plan on doing. He looks at us

stony-faced. "I'm not telling you that you can't do it, but I am telling you

that you shouldn't. I won't give you a permit for any part of it. You'll be

on your own in the Little Colorado - we won't rescue you in there. But if

you make it out, tell us." To be honest, that's the kind of response we're

hoping for. We're in our mid-twenties and think of ourselves as experienced

mountaineers and desert rats. Do we think about floods? Uh, no. Do we think

about quicksand? Sorry. Do we think about injuries? No more than usual. We

know nothing other than that the gorge is about fifty miles long and looks

wild. None of us has ever heard of Harvey Butchart; Michael Kelsey's warning

that the Little Colorado is a "quicksand deathtrap" from Hiking Guide to the

Colorado Plateau is still five years from being published.

The ranger gives us

permission to park a car at Grandview Point, so for the next three hours we

ferry people and our other car to a side canyon, about two miles west of

Cameron, that we're using to enter the Little Colorado canyon. As we're

driving to the put-in point, we pass a hogon. "Shouldn't we ask permission

to leave our car?" I remember someone asking. The consensus answer is "no" -

the hogon appears deserted and our parked car can't be seen from it even if

someone does happen by. We're ignorant - we don't know a thing about Navajo

permits, whether they're required, or, if they are, how to go about getting

one.

Everything gets packed up and we take a group photo: six long hairs wearing

Neil Young "Rust Never Sleeps" 3-D glasses from the Denver concert the

previous year. Quickly dropping through the side canyon to its junction with

the Little Colorado, we note three things: our packs are heavy, between

seventy and ninety pounds apiece; the river is flowing at a pretty good clip

- maybe 200 cubic feet per second; and there are ice chunks floating in the

brown water. The heavy river flow and ice are both unexpected. The Little

Colorado should be dry in winter; that's why we've chosen to do the trip

now. We palaver and decide to keep going - we can always retreat if we have

to.

We're off then, at three o'clock

in the afternoon, and will top out Grandview Point in eleven days. It starts

to rain lightly and, after fifteen minutes, the canyon cliffs out on our

side. A crossing is in order. Being experienced, we have come prepared. We

have special shoes for the occasion: blown out running shoes, tennis shoes,

and Converse All-Stars (it's 1980 - our hiking and mountaineering boots,

which we're wearing, are made entirely of leather and there's no such thing

as a canyoneering shoe). It appears however that some of us are not quite as

prepared as we might be. John doesn't have any rain pants or shorts and

while I have a swimming suit, all I have for lower leg coverage are rain

chaps. Chaps work fine if you're wearing a long rain parka and long pants,

but of course we're taking our army surplus wool pants off and wrapping them

up tightly inside Glad trash bags to stay dry. I probably should have

thought about that a little more. Oh well - there's John, in wool shirt,

white briefs, and All-Stars; here's me, in wool shirt, swimming suit, chaps

tied to shirt tails and drooping almost to my knees, and an old pair of

Adidas. We look like someone's weird fantasy gone wrong.

When Charlie throws his

boots across, one of them dutifully lands in the water and starts floating

down river. He's off like a shot, chasing it as fast as he can on dry land

before wading in and shrieking when he instantaneously sinks in to his

crotch. The rest of us cross at a shallower spot. The water is cold but

we're across quickly. On reaching the other side, we dry off our feet, put

our boots back on, and head off. Two hundred yards later and around the next

bend, the boots are off again for another crossing; three hundred yards

later, another bend, another crossing; a hundred and fifty yards after that,

another bend, another crossing. Hmmm, there appears to be a pattern here -

when the river runs up against something it can't get through, it goes a

different way, and that means we have to cross. Okay - this

taking-the-boots-off-putting-the-running-shoes-on-taking-the-running-shoes-off-putting-the-boots-on

thing is a waste of time. We're just staying in our shoes. For those of us

whose shoes hold together, boots won't come out of the packs again for a

week.

At dusk we emerge from a shallowish walled stretch and look ahead. The river

is braided and spread out about twenty feet wide and a foot deep. We walk

next to it and encounter our first quicksand. Actually, I step right into

it. It is next to the main body of the river at a place where the water is

flowing lazily, about an inch deep. All of the sand ahead looks the same,

but one footstep is solid, the next three are kind of mushy, and on the

fifth I sink into my knees. The others come over and laugh at me. After

squirming around and realizing I'm not going in much farther, they pull me

out. We're losing light and decide to camp. A patch of sand in the tamarisk

is ideal, so we think about but reject putting up tarps (we didn't bring

tents - we're in the desert for goodness sake and it's dry in the desert),

and cook dinner over a tamarisk fire. While it's cold, there is no wind and

everyone stays dry.

Total miles day 1:

4

Day 2:

Rain is spitting lightly

but stops soon after we start hiking. After three hours, we round a

southeast to northwest corner and get a clear view of the next mile or so of

canyon. Where we're standing, the canyon is about one hundred feet deep and

maybe three hundred feet wide at the top. At the next curve a mile further

and a benched layer deeper, it's more like six hundred feet deep and a lot

narrower. We can't see the bottom. Debate ensues: stay on the bench or

follow the river course? Ron's all for the river because he's worried about

getting cliffed out on the bench and having to climb down through rotten

sandstone or limestone. We have a fifty foot rope, biners, and some webbing,

but nothing more. After scouting out the high road option and discovering

that there is no way into this canyon within a canyon from the side, Ron and

I return to inform everyone that we're going to have to get in the river.

While the Little Colorado and Colorado rivers have cut spectacular gorges,

the Little Colorado River Gorge drops only 1700 feet in its entire fifty

mile run from Cameron to the confluence with the Colorado. At the same time,

the canyon incises a canyon that at Cameron is less than a hundred feet deep

and becomes at the confluence 3800 feet deep. The difference between the

height of the canyon walls at the confluence and the river's drop over its

run through the Gorge is 1800 feet, equal to the amount of uplift between

Cameron, at 4200 feet, and Cape Solitude, right above the confluence, at

6000 feet. The result is that, despite getting ever deeper as it cuts

through strata of sandstone, the Little Colorado doesn't drop over twenty

feet at a time anywhere in the Gorge and, until Blue Springs, doesn't even

have many rapids. Its lazy demeanor through the first half of the Gorge

allows it to carry and drop tons of sediment, which makes for completely

undrinkable water but good and plentiful quicksand and mud.

While the Little Colorado and Colorado rivers have cut spectacular gorges,

the Little Colorado River Gorge drops only 1700 feet in its entire fifty

mile run from Cameron to the confluence with the Colorado. At the same time,

the canyon incises a canyon that at Cameron is less than a hundred feet deep

and becomes at the confluence 3800 feet deep. The difference between the

height of the canyon walls at the confluence and the river's drop over its

run through the Gorge is 1800 feet, equal to the amount of uplift between

Cameron, at 4200 feet, and Cape Solitude, right above the confluence, at

6000 feet. The result is that, despite getting ever deeper as it cuts

through strata of sandstone, the Little Colorado doesn't drop over twenty

feet at a time anywhere in the Gorge and, until Blue Springs, doesn't even

have many rapids. Its lazy demeanor through the first half of the Gorge

allows it to carry and drop tons of sediment, which makes for completely

undrinkable water but good and plentiful quicksand and mud.

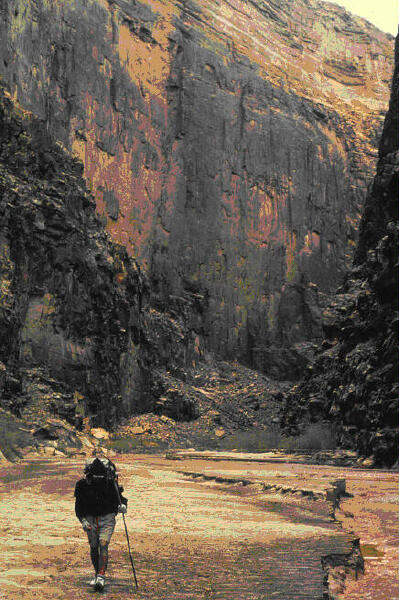

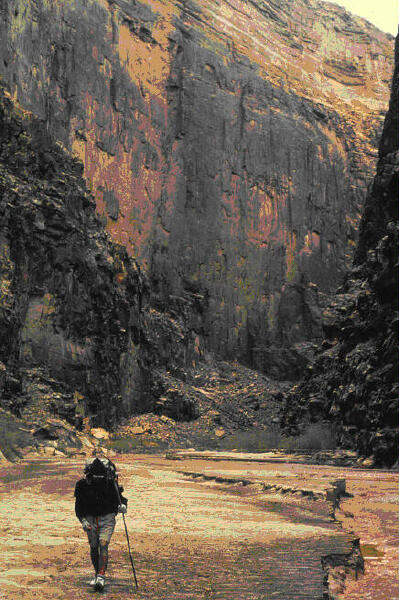

In the canyon within the

canyon it's only fifteen feet wide, dark, and cold, really cold. We're in

the water most of the time for the next mile, usually up to our knees and

sometimes higher. It's cloudy and the air temperature is about 40 degrees

Fahrenheit. Luckily, the exertion keeps us from shivering too much. At some

holes we go in up to our waist, and we find plenty of quicksand, always in

the same kind of setting, next to the river where the water is barely

flowing. This section may be what Kelsey calls "Quicksand Alley." Frank goes

in and works his way up to his navel, laughing like a hyena the whole time.

It takes a considerable group effort to get his idiot ass out of the muck.

About an hour later, while Ron and I are in the lead and out of hearing

distance, Gary sinks up to his neck and is prevented from disappearing

altogether only because Charlie, who is walking next to him, snatches the

bar at the top of his frame pack and keeps his head above the sand long

enough for John to come over and yank him out. That sends a strong and

unambiguous message. Someone comes up with the bright idea to use probes on

the river crossings and to walk single file behind the leader. We

immediately implement the practice and keep to it until we no longer have to

walk in or immediately next to the river.

For the rest of the day,

the Little Colorado continues its cut through Coconino sandstone. I don't

remember any large drop-offs requiring rappels in this section, but I do

remember a longish section of sloping slick rock bench with the river

flowing right over the top of it (I've seen that other places, so maybe I'm

misremembering it). This part of the canyon is continuously extraordinary.

The walls get taller and taller, dead vertical to slightly overhanging,

narrowing the canyon both at the bottom and the top.

John's been complaining about being cold for most of the day; by three

o'clock he's slowing down, stumbling, shivering violently, and slurring his

speech. Experienced mountaineers that we are, even we recognize hypothermia

at the point when the victim becomes incompetent. It must be time to stop.

We're near our planned camp for the night anyway, at a southeast to

northwest turn in the canyon close to a gauging station, so we set up on

sand on the north side of the river under a large alcove where there's no

need for tarps. Across the river - thirty feet or so - the wall rises

directly in an uninterrupted sweep of outwardly veering sandstone for at

least eight hundred feet, stained with six hundred foot long ribbons of

desert varnish. Getting John into his sleeping bag takes about five minutes

and, over the next couple of hours, he regains his core temperature. The

rest of us hang out, talking. By the time he recovers, the light is gone.

Total miles day 2: 8

Days 3-7:

The next five days have

more or less merged in memory into one long, ever-deepening, ever-expanding,

day. I typically rise first and blow the embers from the previous night's

fire back up into a cooking fire for breakfast. We eat, have something hot

to drink, scatter ashes, and start another day of walking next to the river,

still flowing strong but now ice-free. The weather improves to tolerable

hiking conditions - mostly cloudy and about fifty with cool nights in the

twenties. After our quicksand encounters during the last two days, we've all

found stout sticks to use as probes. Wherever we're a little doubtful, we

proceed with the sticks in front, prodding and poking the unseen river

bottom. There's plenty of the stuff, but with a couple of exceptions we

avoid getting trapped, and even those exceptions aren't as scary as what

Gary experienced.

On the other hand, the mud is quite irksome, much more so than quicksand.

Our shoes and lower legs are completely coated in muck. Every time we cross

the river some of it rinses off, but because there's so much of it where we

need to be walking, we inevitably post hole through more, and post holing

through mud isn't like post holing through snow - it's sticky, slippery, and

grabs our legs in a vice grip. Clearly, a major flood has occurred within

the last month and has brought huge amounts of detritus and silt-laden water

down the canyon. We're walking through that flood's drying remains and, as a

result, the going is considerably slower than expected. We can't walk

downstream in the river itself because the water is often too deep and even

where knee-deep or less, it is so completely opaque that we can't see where

we're putting our next foot. Our fear of taking one wrong step and getting

sucked under by mud or quicksand is so fully engaged that we do whatever we

can to stay out of the river and go way above the merely cautious when we

cross.

Since the river itself is

not navigable, whoever is on point has to figure out how we're going to get

downcanyon. For various reasons, most of them having to do with the fact

that we're the tallest, Ron and I do a lot of the leading. It's hard work.

After half a day of leading, we usually have a headache from making so many

decisions. At any point, we have to determine in 50-or-so-yard-segments

whether to cross the river, and where (after several false starts) to do it,

whether to go for the slightly less dense than usual thicket of tamarisk

(and whether or not this will leave us at a river pool), whether to traverse

the base of a cliff and risk it cliffing out, whether to go for the locust

jungles, whether to pass between these two house-sized boulders or those

two, whether to let the rest of the group catch up or not (it's best when

the leader is slightly ahead of the other five so to have time to make

several short backtracks when routes didn't go, so the group doesn't have to

wait).

In two ways the recent flood is a boon - there's lots of driftwood for fires

lying about and, so long as we keep our eyes open for it, we never have to

worry too much about having water even if what we get is awful. We all ran

out of whatever water we had brought with us after the first day in the

canyon, but there are enough streamside eddies full of slowly de-silting

water that we can replenish water bottles at least once a day. The problem

is that the water is nasty. True, it's been settling for a couple of weeks,

but it's gritty, terrible tasting, and a long way from being clean. I don't

remember whether pumps were available then; I know none of us had one. So,

into every bottle we're dissolving iodine tablets that provide a safeguard

but do nothing to improve taste. Our Wyler's drink mixes are lifesavers, but

even they can't cut the grit or the underlying queasiness we feel about

putting this solution in our stomachs. We don't drink a whole lot and are

constantly on alert looking for good water. There isn't much.

Midway through this five day stretch, right below Hell Hole Bend, Gary slips

while jumping from a mud-covered rock and badly torques his knee. We don't

consider going back for long. He reassures us that he will be fine in a

couple of days, so we put together a splint of driftwood and webbing and

continue down-river. My memory suggests that we managed around five miles a

day through this stretch, camping below Hell Hole Bend on the fifth night,

just west of Point 5454 after the river starts running north on the sixth

night, and at Waterholes Canyon on the seventh night, after chasing a family

of deer down canyon during the afternoon.

Each one of the days in

this stretch has some misadventure. At the end of what must have been the

sixth day, we come to a particularly bad river crossing where the river runs

wall to wall for at least thirty yards. We have to cross twice in that

thirty yards, but the river is sluggish, muddy and deep. Ron tries crossing

several places and at each the water rises immediately to his thighs. It's

getting dark. Gary, in a full rain suit, a limp, and a full pack, wades out,

trying to get to a rock near the far shore. He sinks in up to his thighs as

well. We have just started to understand that boulders in the water have

deep holes carved around them by water action. So he jumps for the rock.

Luckily, he reaches it, but he is now stranded, straddling a rock with

over-the-head water surrounding him on all sides. We decide to camp where we

are and rescue him. Ron, Charlie, John, and I gather wood for the fire Gary

will soon need. Frank pulls out some webbing, manages to rescue Gary's pack

without it getting wet, and then tries to help Gary off the rock. As we're

standing next to the fire about twenty yards away, we hear a large splash

from the river and wonder whether one or two have gone in. Gary comes

sloshing up, his hair dripping. He is followed by Frank and his pack, which

is dry as a bone. We all break up laughing.

The seventh day starts

badly, for we have to complete the crossing. Ron scouts it out and discovers

a complicated way along the thirty yards of cliffs on our side. Taking his

pack off, he wades in and again sinks in the mud. Rather than go in any

further, he chimneys up behind a fifty foot tall boulder. Once on top, he

climbs back down a few feet to a bench and lowers webbing to haul the packs

up. Without packs, the rest of us wade over and climb up the chimney. We put

our packs back on and begin a sixty foot ledge crossing. The middle twenty

feet are narrow, completely exposed to the river almost a hundred feet

below, and covered with a ceiling, providing about three feet of clearance.

We have to crawl on our knees, the rock gently nudging us and our packs

outwards toward the edge. All in all, it takes about an hour and a half to

traverse 90 feet of canyon, but it saves two submarine crossings. It's also

apparent to everyone that we we'd be lucky to get back across that traverse

without an accident.

Towards dusk, we have to

cross the river for the umpteenth time. Frank tries a dangerous crossing,

slips, and falls into the river. After getting back up, he gets cliffed out

by a huge boulder at the far side and has to be rescued. Meanwhile, the rest

of us wade at a bad spot and John steps into some quicksand, falls forward

into the water, pulls himself out, swearing up a storm and pouring a quart

of water out of his boots, which had been on the outside of his pack. That's

it - we're done for the day and again make camp in a sorry spot with an

excellent beach in view across the river. We've discovered that we're not as

far as we thought (this is back in the day of 15 minute quads, which don't

show a lot of detail - besides, except for Hell Hole Bend, one bend on the

map looks pretty much like another). What with the mud-induced pace and the

various challenges we've run into, we're at least two days behind where we

should be. If we keep eating the way we've been eating, we'll run out of

food before we get out, so we decide to scrimp a little each day. Overnight

it rains. We stay almost dry under the tarps, but most of what we are

wearing is sodden and will remain that way for a week.

Total miles days 3-7: maybe 25

Day 8:

We expect finally to

reach Blue Spring this afternoon after a seven mile hike. After three

pleasant days in the fifties, the air temperature has dropped back into the

lower forties, with leaden skies and a strong breeze. As it turns out,

today's walking is just more of the same old, same old - lots of mud, a

dozen or more sketchy river crossings, and constant vigilance for potholes

and side canyons so we don't have to drink what we're carrying. There's

almost none of the first, absolutely none of the latter. So, we've been

looking forward to camping at Blue Spring because the name sounds appealing

and because we're expecting it to provide high quality drinkables.

The canyon becomes

unusually tight and a little chaotic - boulders and rocks litter the river

bed and negotiating them takes time. Late in the afternoon, we reach a

spring, immediately identify as the Blue Spring, and declare the day's

hiking over. It is quite interesting visually. The aquamarine water emerges

at the top of the Redwall Formation, pumping about 50 cubic feet per second

from springlets in and near the river bed and a couple of much larger

springs immediately next to it. The flow introduced from the springs

transforms the Little Colorado from an intermittently running stream into a

permanently flowing river and adds the minerals that make the travertine

dams for which the lower stretches of the Gorge are well-known. Since the

river is flowing heavily already above the springs, it's brown again five

feet below them. But the water itself is god awful -oily to the tongue and

alkaline to the taste buds. For reasons that remain unclear to me even now,

we call it 'sweetwater.' We cook with it for three days and drink it with

lots of Wylers lemonade powder added to it. Even then it gives some of us

the runs.

That evening Ron and I cross the river to get a closer look at the spring we

can see from our campsite. We wade out without pants and are soon in up to

our waists, so we take shirts off and try again. Up to our navels this time,

but we make it. The spring gushes from some cracks in the limestone and

forms three or four bathtub size pools, then flows away. The water is

slightly warm and we sit in it. Hey, that feels good - anything is warmer

than what we've been used to for the last five days. While I return to camp,

Ron scouts downstream, finds another large spring, and then comes upon the

really big one - a series of three ten-foot deep pools, clear and

aquamarine, and flowing slowly but with great volume, probably 200-300 cubic

feet per second. He wades in front of them, walks some more beach, notices

another crossing that will have to be done in the morning, and returns in

the gathering darkness. It rains again overnight.

Total miles Day 8: 7

Day 9:

This is the first of

three hard days: by dusk, we will have managed all of three miles. We start

off in rain pants and wool sweaters, and regularly wade up to our navels.

Half-way through the day, we are forced by cliffs on both sides to cross at

a bad rapid. I lead into waist deep water and a strong current, trailing two

long pieces of webbing. I find a rock midway in the river and set myself up

as an anchor. Ron holds the other ends of the webbing and sends the others

across to me one at a time, each holding the webbing as a hand line. Charlie

slips into a deep hole, goes up to his neck, and then jumps for the rock.

Ron is last and has only the end of the line in front of him. He too jumps,

slips, and gets soaked. Once we are all huddled around and holding onto the

rock, I lead the easier second half of the rapid and everyone else follows.

We build a lunch fire and try to dry our sweaters. The afternoon produces

more deep but "easy" wades, with one exception. Ron feels out a crossing and

steps off a sandbar into a mud hole. He has to take a couple of breast

strokes back to shore before trying somewhere else. We can't wait for sleep

to end what has been a miserable day.

Total miles Day 9: 3

Day 10:

We hope to make it to the

Sipapu, where the Ancient Ones emerged into this world. It's about eleven

miles away. With an early start, we'll be there just as it's getting dark.

Well, it's a good idea, but it is not to be. By early afternoon, we're at a

point where the river makes an 'S' turn, from going almost due north, to

going southeast, to going almost due north again in a straight shot to Big

Canyon. We encounter the most serious rapid we've seen so far - it's

actually kind of big, Class III, maybe Class IV, and it continues for a

hundred and fifty yards all the way around the north to southeast portion of

the 'S'. Of course, we have to cross it. An enormous gust of wind roars down

canyon over us. It dies down for two minutes and then another gust comes

down canyon. This time the wind doesn't fade - it blows a steady twenty-five

miles an hour with gusts to fifty. Charlie and Gary are looking for a place

to cross the rapid at its rockiest place, near the top; Ron, John, Frank,

and I have chosen to cross it at its narrowest point about fifty yards

downstream from them. The river slams into a cliff thirty yards below us.

Ron has a good idea: set

up the rope across the river, then, using it as a zipline for the packs and

a handline for the people, get across. It is twenty feet to the other side,

with maybe eight feet of serious current to worry about. I offer to go first

and tie the rope around my waist. I get to the edge and, holding onto a rock

to brace myself against the current, test for the bottom. Nothing. I test a

little deeper - ok, it's there and I'm in past my navel. I put my foot out

for another test plant, and step into nothing but deep, fast water. WHOOOP!

- I'm completely submerged before I know it and then my pack pops me back up

like a cork. Shit - I'm heading downstream with a rope tied around my waist.

This is not good. Luckily, Ron has the good sense not to reel me in (pulling

against the current would drag me right into and under the fastest and

deepest section of water). I thrash and yell and splutter and blubber and

kick my way to the opposite bank and emerge about twenty feet downriver,

soaked to the bone.

I return to our crossing

point. We use meat belays on both sides to tighten the rope six feet above

water level and on a slope to me. John's pack comes across hanging from a

biner, dragging through the water for the last six feet. This job takes just

enough time for me to start to chill down. When John comes across, he's

white with fear and I'm chattering away doing a full body shiver dance. He

is swept off his feet twice and barely makes it. Then it's Ron's turn: the

current lifts his feet and he too does a face plant into water. Finally, the

three of us just haul Frank across, but I'm shaking so hard I can't do much

of anything. Someone yells at me over the rapid's roar to get out of my wet

stuff and into some dry clothes. Ron and Frank go looking for Gary and

Charlie upriver while John and I shoulder packs and head for higher ground.

The others' packs and the rope stay propped up against the bank where I put

them.

Between the river's edge

and the sand bar that I'm headed for is a fifty foot wide swath of broken

ground that would be inundated were the river to flood. I strip off my

swimming suit, T-shirt, rain jacket and chaps and try to get into my dry

wool shirt, dry wool pants, and dry wool socks. But I can't button my shirt

or zip my pants, and every time I try to put on a sock I fall over. Fuck it

- I put my down booties on over bare feet and slip a down jacket over the

unbuttoned shirt. That's better. Still shaking violently, I climb up the

eight foot sand bar. It's perfectly flat on top and sparsely covered with

grass. There's some wood lying around, a few smallish junipers, and a couple

of other larger bushes of some unknown species. The air temperature is

dropping and it's spitting rain sideways. I'm still shaking, but it's

getting less violent and as long as I keep gathering wood it will end. Gary

and Charlie show up, wet to the neck. One of them starts a fire with stove

gas. The other three arrive shortly after, all of them soaked and shaking.

Frank, Charlie, and Ron return to the river to retrieve the packs and the

rope, while John, Gary, and I huddle around the fire and lay out shoes and

clothes to dry.

When the others return with the packs, Ron mentions that some of the rope

was in the water when he found it. I guess I must have left it like that;

good thing it didn't float away. We take stock of our situation and debate

whether to continue. It's probably three o'clock. The wind has subsided a

little and it's begun to rain, not hard but steadily. The spit we're on is

thirty feet long, ten feet wide, and attached to the southern wall of the

canyon like a portaledge. From the back of the spit, where we are, we can

see downstream a little ways but not upstream at all. The edge of the spit

drops eight feet to the floodplain, which narrows from the area of the creek

crossing and pinches off completely near our peninsula's downstream limit.

Further down, about a quarter mile away, the river completes its 'S' by

turning northward and passing through a rock gate that is perhaps seventy

feet across, with three hundred foot walls rising directly from the water on

either side. Above that, the remaining terraces, walls, and benches ascend

unseen 2500 feet to the top of the canyon.

Since the river turns as

it passes through the gate, we can't see any further downstream, so we pull

out the topo map, which suggests that it runs in a straight corridor for the

next three or four miles to Big Canyon. If the corridor continues to Big

Canyon the way it starts - seventy feet wide with three hundred foot walls

on each side - then, given what we've encountered in the last two days, if

the river floods big we could easily get trapped. However, and again given

what we've encountered in the last two days, if the river floods big and we

can't get through the corridor, we'll be trapped where we are now, with no

escape upstream or downstream. All things considered, we're in a tight spot.

Charlie volunteers to

sneak a peek downstream. He's back in less than two minutes - he reports

that the river is already out of its banks, onto the floodplain, and rising

fast. Well, that makes the decision for us: we'll stay put at least for the

night. So long as the river doesn't rise more than ten feet, that is, so

long as the flood isn't biblical, we'll be okay on our little sand spit for

a couple of days before we're out of food. We set about collecting all the

available firewood and putting up the tarps before it gets dark. We have

barely enough water to boil dinner and none at all for breakfast. I couldn't

care less. I feel like my wool sock hanging over the fire - shapeless,

floppy, and impregnated with sand, mud, and water. The drizzle continues

through dinner, comes and goes for about two hours afterwards, and then,

after we're in our sleeping bags, changes to a hard, continuous rain that

lasts all night. Squeezed under the tarps in all of our available wool

clothing, we're as smelly as wet sheep. Living the dream, for sure.

Miles day 10: 4

Day 11:

When we awake, it is of

course still raining. No one has slept well and everyone is wet from various

tarp leaks we were too tired to deal with overnight. Charlie and Ron are

wetter than the rest of us. Not that it really matters - we're all about to

get drenched. I walk out to the upstream end of the spit and look at the

river - it's spread across the floodplain, lapping the escarpment we're

marooned on. Luckily, the water is still six feet from the top where our

bivouac is located. It's an impressive and unnerving sight.

Charlie plants a stick in the floodplain to gauge the water's behavior and

returns to the tarps for breakfast. After eating, it's decision-time: do we

wait it out until the water recedes or do we go for it? We look down-canyon

- the river is running wall-to-wall through the gate and this time there's

no high route around it. Charlie returns to look at the stick in the

floodplain. It has about the same amount sticking out as half an hour ago.

Good, at least the river isn't rising quickly. That factoid becomes part of

our deliberations. After a surprisingly short discussion, we decide to give

it a whirl - if it's too dangerous we'll come back and wait the flood out.

We're low on food, but there's a runnel of rainwater coming down the wall

near camp that we can lap at until things dry out. That's all we really

need. Worse case scenario is the flood gets a lot bigger and washes us all

downstream. But that's not likely: there's no evidence that floods ever wash

this high. So, if either the current is too strong or the water is too deep

to stand up in, we're coming back; otherwise, we'll see what happens.

Charlie, John, Gary, and Frank are ready to go first and walk to the

upstream end of the spit to get into the water on the floodplain. Ron and I

follow. Okay, it's up to my stomach, maybe three and a half feet deep, with

a relentless current. I look upstream for some reason - something biggish is

being carried through the rapids. It's not a tree or a bush. It can't be

that heavy, but it's as big as - oh for Christ's sake - a cow, a dead one,

bloated, feet sticking straight out and into the air, bobbing on top of the

water like a rubber duck in the tub. Ron, who's on top of the spit

immediately above me, sees it and laughs - "maybe we should try to lasso it

and use it to float our way out of here." Not a bad idea, if you think about

it. And then its stench hits us square in the nose - all right, not such a

good idea after all.

Frank leads us toward the gate. With our probe sticks as underwater eyes and

walking in strict single file six feet apart, constantly updating each other

on conditions underfoot, we wade in. The river gets gradually deeper until

we're up to our chests and necks, being pushed insistently downstream. To

the extent that our trash bags are still dry bags, our packs are riding up

on our shoulders and provide some buoyancy: with a little practice, we kind

of bounce from step to step without being pulled up and off our feet or

being pushed over by the pack's weight. It's cold in the water, but since

we're now lower than the rapids, the river is about as level as it can get

and still flow. Thankfully, the river bottom is sand and not mud.

Frank peers around the corner and shouts back that the river is running wall

to wall for at least three hundred yards. Beyond that he can't see well

enough through the rain. It's a huge relief that there aren't any more

rapids. Then he's laughing hysterically - as always, a sure sign that

something's wrong. He's dog-paddling trying to keep his head above water.

Gary, next in line, follows suit. I'm next, but I avoid the hole they've

fallen into. I move a little to the westward cliff and, while I go in up to

my chin, I'm able to continue bouncing off the bottom. Ron and John follow

me, but Charlie ends up swimming.

I don't remember anyone ever suggesting that we return to the sand spit. It

would have been moot anyway - the current is too strong to walk against

going upstream. Had we brought along inner tubes or inflatable mattresses we

could have just loaded our packs onto them and hung on. But of course we

hadn't thought of that. Everyone is super careful; we all know that going

down the river is our only option and that doing anything stupid will

endanger everyone. And so we continue, walking, bobbing, swimming,

thrashing. My memory suggests that things went on like this for maybe half a

mile, at which point we found a place to beach ourselves briefly on the

eastern shore. But that doesn't last long and we're soon in the water again.

I do not let on to the others how worrying I think our situation is. If

anyone is swept off his feet or gets caught by something underwater, the

rest of us will be able to do nothing more than yell at him to dump his pack

before it has the chance to push him under. The image of watching one of us

disappear competes in my mind with the vigilance needed to make sure that it

isn't me.

The river continues to flood over its banks here and there and, what with

the canyon walls streaming with water, there is less walking and more

swimming at each crossing. By now, our packs and most of their contents are

getting pretty wet. While they still float, they are no longer buoyant

enough to pop us back onto the surface were we to fall into a hole. The

water at the final four crossings, each immediately above large travertine

dams, is well over our heads, probably nine or ten feet deep. We knot the

rope and webbing together and tie each guy in before he enters the water to

ensure that we can drag him out if necessary. And then, one at a time, each

of us kicks our way across, pushing our packs in front of us like floaty

toys.

All we want is to get to

the confluence without having to cross this damned river again. But there's

no way we're going to make it today - at the rate we're going, it will be

dark before we get half way. Running on anxiety and adrenaline, we stumble

and bumble our way past Big Canyon. At Salt Trail Canyon, the first good

thing to happen in three days occurs: the rain softens into a mist that

hides all but the lowest three hundred feet of the canyon. And then, quite

suddenly, something even better happens: fragments of a trail appear. My

brain re-ignites from its gloom and doom circuit. Ding-ding-ding! A trail

can come from only one direction - downriver - and it can be made by only

one kind of critter - day hikers walking upriver from the confluence. Like

magic, my dread about what's around the next corner begins to dissolve and I

find myself in a semi-dream state of overpowering relief. The world becomes

hospitable again - instead of being redundant evidence of our dire

situation, the dozens of waterfalls surrounding us now emerge miraculously

from cloud vapor above and cascade down glistening canyon walls in an

extraordinary display. And the flooding Little Colorado is no longer a

menace but a spectacular event that we're privileged to see up close. As I

wrap my brain around the thought that we're probably not going to have to

cross the river again and that we will get to the confluence after all, the

adrenaline dump begins, not just for me but for everyone. We stop under a

huge overhang, get a fire going, and watch the smoldering wood.

I don't remember much about the rest of the day except that despite the

canyon walls running with water, we have nothing to drink. Ron and I

eventually volunteer to fill bottles and find a big pothole full of clear,

clean rainwater up a side canyon. We're now four days behind and sapped, but

we're alive and more or less uninjured. Dry under the overhang and more at

ease than we've been in days, we collapse, without dinner and before dark,

into sound sleep.

Miles day 11: 5

Day 12:

The day dawns cloudy, but

brighter and noticeably warm. The river has receded overnight and is more or

less back in its banks again. We should be driving home today, but we

haven't even made it to the confluence of the Little Colorado and the

Colorado, let alone to the base of the Tanner Trail, which is fifteen miles

distant, on the other side of the Beamer Trail. Given our condition, getting

to Tanner Beach today isn't viable. We decide instead to get to Beamer's

rock house at the confluence five miles down canyon.

Within an hour of

starting down the now distinct and continuous trail, we see the Sipapu on

the other side. The sun comes out, and since the river has gone down far

enough that we can cross safely, Frank and I dump our packs, strip down, and

swim across for a look-see. It's a mound that's about fifteen feet tall and

perhaps thirty feet in diameter, chocolate-colored, and more or less flat on

the top. Scrambling up, we discover a hole in the middle of the mound, maybe

fifteen inches in diameter and without any apparent bottom, eagle feathers

stuck here and there into the interior walls.

After crossing back over,

we lounge around barefoot in the sun for some time, confident that the trail

will lead us to the confluence and the rock house. We're now low enough that

the grass is greening and trees are budding. Each of us adopts his own pace

for the rest of the day and we stroll slowly down canyon, sometimes alone,

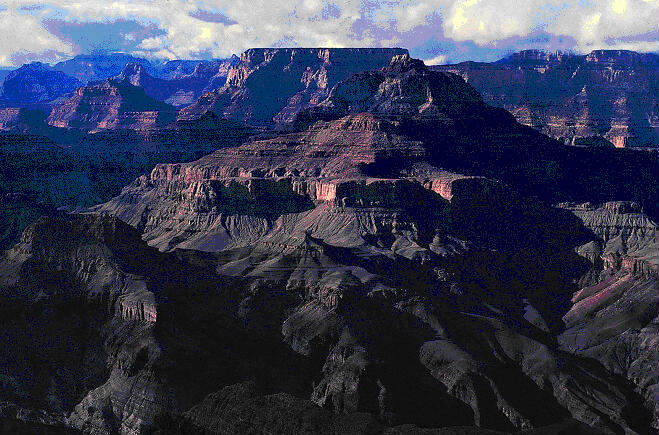

sometimes with one of the others. The Little Colorado River Gorge is for its

last few miles overwhelmingly sublime. I still vividly recall the dramatic

enormity of the canyon - almost 4000 feet deep and multi-tiered, it induces

a paradigmatic experience of insignificance. That night we eat a little

spaghetti with bullion and sleep on long green grass under a clear sky a few

hundred feet from the confluence, a comfortable end to an unforgettable

wilderness day.

Miles Day 12: 5

Day 13:

We expect today to

traverse the Beamer Trail from the confluence to Tanner Beach in the Grand

Canyon; tomorrow we'll ascend the Tanner Trail to Lipan Point. The trail was

built by Ben Beamer, who tried in the 1890s to farm at the confluence.

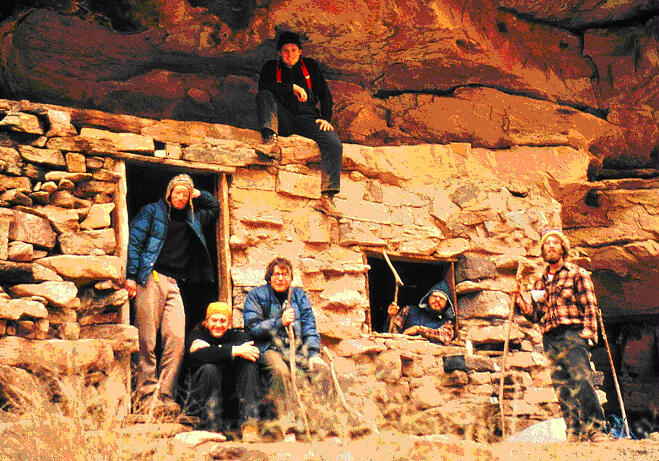

Before starting out, Ron takes a picture of us all at Mr. Beamer's rock

house: we're dirty, tired, and hungry, but smiling.

The Beamer is easy, being almost level for 5 miles as it traverses a bench

of Tapeats Sandstone immediately above cliffs that drop to the Colorado

River. At a few places the trail is indistinct or washed out, and for one

hundred yard stretch, it is so degraded that we walk across a twenty degree

slope of bare dirt and pebbles no more than three feet from the edge of a

five hundred foot drop straight to the river. It's plenty spooky. Ron,

Frank, and John cross on a higher contour where the angle and exposure are a

little less severe. What a place this is - the Palisades of the Desert soar

3000 feet directly above us and, across the river, Chuar and Temple Buttes

on the North Rim loom even taller. As intimidated as I feel being here, this

stretch of gorge along the Beamer is rather narrow, so the jaw-dropping size

of the Grand Canyon remains veiled. And since the trail requires us to be

attentive - it feels like we're suspended on a highwire between canyon rim

and river - I'm not sure any of us noticed much of that grandeur anyway.

Eventually, we reach easy hiking and drop off the Tapeats bench to the river

at Lava Canyon Rapids and Palisades Creek. Hunger and the inevitable

relenting of vigilance that accompanies our return to less exposed ground

again begin to take their toll. We slow way down and marvel as the Grand

Canyon opens up directly in front of us. Occasionally we catch glimpses of

the North Rim five miles away, shrouded in cloud and new snow. After the

100-yard widths of the Little Colorado canyon, the incredible vistas of the

Grand Canyon seem completely unreal, like living in a refrigerator box for

10 days, then suddenly popping your head out and seeing the whole back yard.

By the time we get to Palisades Creek, we're exhausted, too lazy and weak to

finish the final three miles to Tanner Beach. We share some granola for

dinner - the single Rice-a-Roni dinner that John amazingly unearthed in his

pack this morning will be eaten tomorrow - and sleep under the stars.

Miles day 13: 6

Day 14:

It's been a windy night,

but dawn brings another beautiful and warm day in the bottom of the canyon.

We've filled every cooking pot with river water to settle overnight; now, we

filter it through bandanas before leaving and get about a quart a piece. The

water is none too clear and tastes nasty, and we're out of Wylers. Luckily,

it's an easy three miles to Tanner Beach, where we've been told there may be

a spring. Arriving before lunch, the entire afternoon is wasted reading and

napping in the sun, 4,500 feet inside the earth. At dinner we scrounge

everything left in our packs and cook it up with John's Rice-a-Roni for as

big a meal as we've had in more than a week. A long discussion ensues about

the space program, world hunger, transcendental meditation, Buddha, Plato,

Aristotle, presidential powers and the judicial branch, and, of course,

truth. Five hours after going to sleep under the starts, a brief

thunderstorm catches us by surprise. We throw the tarps over ourselves while

it pours, a puddle forming in one tarp right above me. I push the tarp up to

drain the puddle, but instead of rolling off where I thought it would, it

surges over the edge and right onto Frank's sleeping bag. We all laugh at my

stupidity and his bad luck. Nothing matters: we'll be back to the cars and

the dry clothes they contain tomorrow.

Miles day 14: 3

Day 15:

The Tanner Trail is dry

from bottom to top, so we fill our bottles with the spring water at Tanner

Beach. The lower part of the trail climbs steeply, and two weeks of downhill

and level hiking have left our climbing muscles weak. I find it grueling -

when we top out of the Redwall Limestone, I'm dragging behind everyone else

by a good twenty minutes. Someone gives me their last granola crumbs and I

drink some water. We take pictures, agree to go at our own pace on the rest

of the trail, and head up. Anticipating being the last one to the top, I

leave first. Ron quickly passes me, but, as things turn out, I climb faster

and faster and don't see anyone again until trail's end. It's about three

o'clock when I top out. I must have food, but, of course, we can't get in

the car because it's not here - the Tanner tops out at Lipan point and the

car is at Grandview Point, twelve miles away. Shit. Ron heads off, hoping to

hitch. Frank shows up half an hour later and talks a young woman from

California into giving him a ride to the car; they pick up Ron along the

way. Gary, John, and Charlie straggle in over the next two hours.

As we're loading up around dusk, a California pickup-camper rig arrives and

produces a longhair and his wife, both in their 30s, and their two young

kids. We get to talking -they're interested in what we've done and the

husband volunteers to swap us for two of our walking sticks. We agree to the

exchange and get a big tub of homemade yogurt and a couple of oranges. Then

they and we are off - they're headed to Flagstaff and points unknown, we're

going to pick up the other car and return to Colorado. We stop in at the

ranger station to inform them that we're out, but everything is closed up

and no one's around, so we leave a note instead.

We locate the other car

at our put-in point well after dark. Hey, it's not up on blocks. That's a

good thing. But the tank of gas we left in it has been drained. That's a bad

thing. From this, we infer two more things: first, that hogon wasn't empty

after all, and second, we should have asked permission to leave the car

here. Luckily, there's enough gas left in the tank to start the engine, and

there's a Conoco station at Cameron less than three miles away. The car

makes it on fumes and dies near the pumps. We agree that it might be a good

idea to wait right here, so we say goodbye to Ron and Frank, who are headed

to Phoenix.

Miles day 15: 9

Epilogue:

After the trip, we all

returned to school, eventually graduated, and entered adult and professional

life. Frank was on the west flank of Mt. St. Helens the day it blew its top

and got chased down the Toutle River canyon by the mudflow; he's now a

recreational planner for a federal agency. Ron jobbed around on fire and

trail crews before landing a permanent position as a parks and recreation

planner for another federal agency and, more recently, with state and local

agencies. After a year in Jamaica with the Peace Corps, Charlie became an

environmental engineer. John worked in Silicon Valley and then became an

intellectual property attorney. Gary also became an attorney and has

traveled widely with his unique expertise. I'm an academic and just returned

myself from a year in Jamaica as a Fulbright Fellow.

Ron and Gary and I still

keep in touch. In fact, they helped me with this account by reminding me of

events that I'd forgotten and making corrections to some of what I thought I

remembered. I'll see Gary next month when I present at a conference in

Tucson, where he lives. I'm taking my son Calvin with me. Perhaps he and I

will return via the Grand Canyon so that I can take him to the Little

Colorado Overlook and show him the canyon. I might even tell him a few

stories to prove to him that his dad isn't such a boring loser.

[ Homepage ] [ Introduction ] [ Warning

] [ Ratings ] [ Ethics ] [ Feedback

] [ Updates ]

© Copyright

2000-, Climb-Utah.com

|

While the Little Colorado and Colorado rivers have cut spectacular gorges,

the Little Colorado River Gorge drops only 1700 feet in its entire fifty

mile run from Cameron to the confluence with the Colorado. At the same time,

the canyon incises a canyon that at Cameron is less than a hundred feet deep

and becomes at the confluence 3800 feet deep. The difference between the

height of the canyon walls at the confluence and the river's drop over its

run through the Gorge is 1800 feet, equal to the amount of uplift between

Cameron, at 4200 feet, and Cape Solitude, right above the confluence, at

6000 feet. The result is that, despite getting ever deeper as it cuts

through strata of sandstone, the Little Colorado doesn't drop over twenty

feet at a time anywhere in the Gorge and, until Blue Springs, doesn't even

have many rapids. Its lazy demeanor through the first half of the Gorge

allows it to carry and drop tons of sediment, which makes for completely

undrinkable water but good and plentiful quicksand and mud.

While the Little Colorado and Colorado rivers have cut spectacular gorges,

the Little Colorado River Gorge drops only 1700 feet in its entire fifty

mile run from Cameron to the confluence with the Colorado. At the same time,

the canyon incises a canyon that at Cameron is less than a hundred feet deep

and becomes at the confluence 3800 feet deep. The difference between the

height of the canyon walls at the confluence and the river's drop over its

run through the Gorge is 1800 feet, equal to the amount of uplift between

Cameron, at 4200 feet, and Cape Solitude, right above the confluence, at

6000 feet. The result is that, despite getting ever deeper as it cuts

through strata of sandstone, the Little Colorado doesn't drop over twenty

feet at a time anywhere in the Gorge and, until Blue Springs, doesn't even

have many rapids. Its lazy demeanor through the first half of the Gorge

allows it to carry and drop tons of sediment, which makes for completely

undrinkable water but good and plentiful quicksand and mud.