[ Homepage ] [ Introduction ] [ Warning ] [ Ratings ] [ Ethics ] [ Feedback ] [ Updates ]

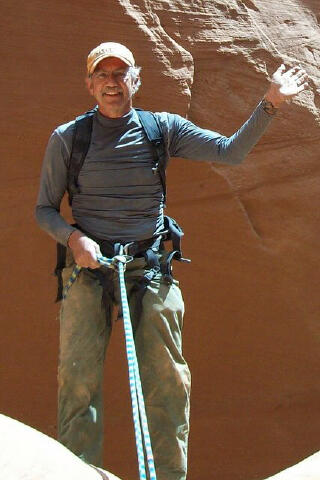

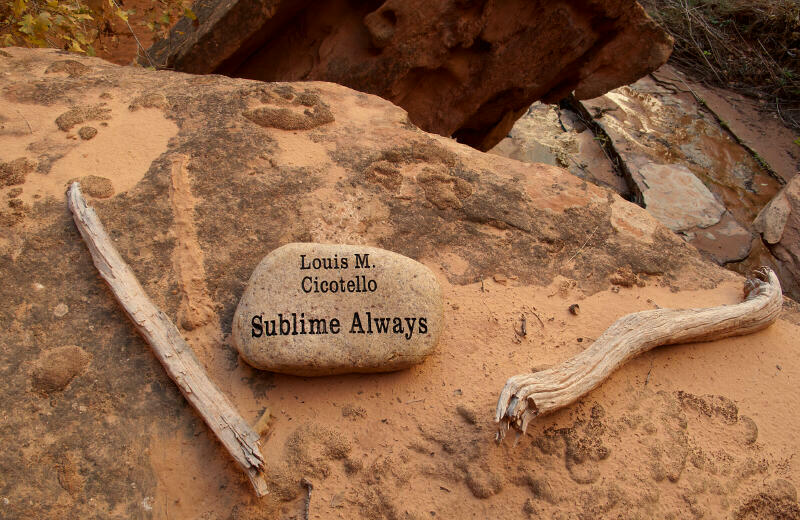

David and Louis entered the North Fork of No Man's Canyon on Sunday, March 6, about 9:30 am. They successfully went through the canyon and reached the last rappel at 1:00 pm. They planned to eat lunch at the bottom of the rappel and then walk up the old horse trail back to the rim. This particular rappel is a two-stage affair, the first part being about 40 feet down to a ledge, the second part being about 100 feet down to the ground. They had a 200 foot dynamic 10 mm climbing rope with them. In rigging the second rappel, Louis threaded a long piece of new webbing (with a rappel ring attached) through a biner clipped into the existing bolt and hanger on a wall next to the ledge. This long loop of webbing extended down from the bolt hanger over a sloping ramp about twenty feet long and almost to the edge where the rappel proper begins. Upon completing the anchor, Louis fed one end of the rope through the rappel ring, located the midpoint of the rope, and threw both strands down. A biner block was not employed and the ends of the rope were not tied together. Louis clipped into the rope using a variable speed ATC. He backed down the ramp to the rappel ring and safely loaded the anchor. Upon reaching the edge, he recommended that David be careful not to get his hands pinched between the rope and the rock as he came over. He then went over the edge from the ramp and informed David that he was on the free portion of the rappel. David lost sight of Louis. A few seconds later, Louis called up to David that he could see that the ropes were unequal but that it was "no biggie." Those were his last words. Almost immediately, the rope whipped through the rappel ring and disappeared out of sight below. David could not see Louis but called out to him. There was no reply. Stranded on the ledge without a rope and desperate to help his brother, David rummaged through his pack and found a length of static rope used to lower packs over short drops, some webbing, and an étrier. He knotted them together and realized that it was not long enough to reach the bottom. He tried climbing up the previous rappel but could not make it. Louis had brought a bolt kit and an Ibis hook, but both were in his pack at the bottom. David was ropeless and 40 feet down from the top of the pour-off and 100 feet above the bottom. He had a liter bottle full of iced tea/lemonade, another small bottle of water, an orange, a sandwich, a high energy bar, some cashews, some matches, a flashlight, a knife, extra wool socks, and a jacket. David figured no one would come looking for him until the following Friday, six days hence. He and Louis were on the second day of a trip that was planned to go through to the next Thursday. They had already done Lost Spring Canyon the previous day and were planning on driving from No Man's down to Cedar Mesa to go through Cowboy and, conditions permitting, Maidenwater. Then they were going to drive back up into the Swell, descend Music, and finish the trip with Greasewood Draw as dessert before checking into a motel on Thursday night and calling loved ones. David determined then and there that he would have to survive until Friday. He took his pack apart, removed the foam back, and began his vigil. He allowed himself two ounces of water or tea per day, one segment of orange, a bite or two of sandwich and energy bar, and a few cashews. At night, he collected detritus from the ledge and started small comfort fires. He inserted the foam pad under his shirt to keep his core body temperature up. Attaching the wool socks to his baseball cap allowed him to keep his ears and parts of his face warm at night. During the day, he watched animals and birds come to the pool at the foot of the big rappel to drink water, and each night a bat flew out from above him on its nightly rounds. David had left with his girlfriend a detailed map of their camps and the nights they intended to spend at each. On Friday morning, David's fiancée called Louis' wife in Colorado Springs and the two of them called Hanksville BLM, the San Juan County sheriff office (Cowboy), the Emery County sheriff's office (Music and Greasewood), the Wayne County sheriff's office (No Man’s and Lost Spring), and anyone else they could get hold of to hear out their concerns. Since I was familiar with these areas (Louis, David, Ted, Mike, and I have done more than fifty canyons together, although we had never been down No Man's), late on Friday I emailed details about each camp and each trailhead to Louis’ wife, who then forwarded the email to the SARs and sheriffs. Wayne Country SAR got a helicopter up that night and, with all of our information in tow, flew over the No Man's drainage, locating Louis' truck at the trailhead. David heard the helicopter that night and knew that he was going to be rescued. He had thrown out the last few bites of his sandwich on Wednesday when it had rotted, and he tossed the small amount of remaining tea on Thursday after it became rancid. By Friday evening, he was down to an ounce of water, a few cashews, and one slice of orange. He told himself he would not drink that last ounce until he heard a rescuer call his name. Reason: he refused to look at an empty water bottle. Under the leadership of Sheriff Ernie Robinson, Wayne County SAR was on the scene first thing Saturday morning. Ted, Mike, and I left Colorado Springs at 8:00 that morning. We caught up with Louis' wife at Ray's Tavern at about 2:00 pm (she had caught the 6 am flight to Grand Junction and rented a car). Thank goodness for cell phones – as we were driving, we were on the horn with Louis' wife, Dave's girlfriend, and the search team on-site. We talked with both Sheriff Robinson and the helicopter pilot and suggested that they focus exclusively on the North Fork of No Man's, and, in particular, inside the slot rather than any of the surrounding country. Sheriff Robinson sent in a team from the top and landed a team down below the big rappel. Flying back up the drainage, the pilot spotted a long piece of webbing protruding from the ramp on the middle of the big rappel. David had fashioned a HELP sign from parts of his equipment (webbing, his foam pad, some tape, and a couple of biners) and was dangling it at the end of the webbing. The helicopter passed over once, twice, and then a third time. Within an hour or so, David heard the team coming up from below and called out. The team coming down from above rescued David soon after. He was immediately airlifted to Moab hospital at about 1 p.m., rehydrated, and released that evening. The four of us -- Ted, Mike, Louis' wife, and I -- were in Hanksville by 2 pm, where we were met by Sheriff Webster. He informed Louis' wife that Louis had not made it but that David was alive. We drove out the Roost Road and had just turned toward the South Fork of Robber's Roost and the Ekker ranch when we saw a helicopter fly over, heading to No Man's. Arriving ourselves there a few minutes later, we were introduced to Sheriff Robinson and watched the helicopter lift off down canyon to recover Louis' body. An hour later, the helicopter returned with him. Sheriffs, search team, helicopter, and the four of us caravanned out of the Roost together right at sunset, reaching Hanksville about 8:30. We talked with David for the first time later that evening. This is an extraordinarily difficult time for the families. David’s incredible endurance, intelligence, loyalty, and toughness are immediately countered by Louis’ tragic death. The family is grateful for all the condolences and well-wishes received. We would like to express our deepest thanks to Sheriff Robinson, Sheriff Webster, Sheriff Micah (sorry, we don’t know Micah’s last name), and all the other members of the Wayne County Search and Rescue team. They worked tirelessly, professionally, and expertly to save David’s life and recover Louis’ body. We would also like to thank Magleby Mortuary in Richfield for their equally professional and expert service to Louis’ wife. It will come easily to some in the canyoneering community to speculate about what happened after David lost sight of his brother on the second stage. David doesn’t know. I don’t know. You don’t know. David reported that Louis voiced no concern when he mentioned the short end and that his last words were “no biggie.” Louis never cried out, his voice never trailed off, and his landing was not loud. There was no damage to the rope or to his ATC. These facts suggest to David, Ted, and me that Louis may have made it a good way down the rappel before something went wrong and that he may have been trying to jump the last few feet when he rapped off the short end and landed badly. But this is a best guess only and admittedly one fueled in part by wishful thinking. It will also come easily to some in the canyoneering community to speculate about whether this accident could have been avoided. No doubt it could have been. But the woulda-coulda-shoulda game that inevitably follows an accident of this sort should be tempered by the following knowledge. Louis was an expert mountaineer, a 5.10 rock climber, and, until this accident, a reliably safe canyoneer. He had probably done more than 600 rappels. True, he was 70 years old, but he had the body of a 50 year-old marathoner -- a little bruised and battered but structurally sound. He had been climbing for more than 30 years. He had been a desert rat for at least 25 years and a canyoneer for the last 13 years. He did three or four desert trips a year, some technical, some non-technical. On our trips he usually set the anchors because he was so meticulous about it, making sure to balance forces and establish redundancies wherever possible. We always checked each other’s anchors, set-ups, and clip-ins. It’s true that Louis didn’t knot the rope ends before the last rappel. We don’t know why – we typically did on longer rappels and on rappels with blind landings. We suppose also that he could have used a biner block at the rappel ring. It certainly wouldn’t have been foolproof, but it might have worked if, as we suspect, he rapped off the short end a little higher than he had been anticipating. No doubt others can think of even better Monday morning solutions. Louis loved canyoneering and enjoyed reading the canyoneering websites and keeping up with the latest news. He communicated with Shane Burrows and Ryan Cornia on beta on a few occasions. For reasons that neither of us understand, we’ve never met any of you Bogleyites or Yahooians out in the boonies. We’re sorry that you never had the opportunity to get to know Louis, for we believe that had you known him you would miss him as much as we his family and friends now do. He was an extraordinary man – a Yale MFA in sculpture, much-loved professor and former chair of the Department of Visual and Performing Arts at the University of Colorado Springs, astonishingly good chef (we ate like kings and queens on our trips), devoted husband to his wife Millie Yawn and a marvelous father to their daughter Sarah. Two years ago, Millie and Louis welcomed their first grandchild, Olive. He was enthusiasm incarnate. He was also constitutionally generous, kind, intellectually wide-ranging and deep in his areas of expertise, and hilariously funny. Louis taught my twelve year-old son Calvin how to clean a fish and he helped rescue Calvin from the bottom of Munchkin last year when Calvin got his foot stuck. If I may, I’ll let Calvin have the last word: “he was one in a trillion, Dad.”

Newspaper Account: MTSU official rescued after being

stranded in Utah cave for 6 days

Related Link: [ Homepage ] [ Introduction ] [ Warning ] [ Ratings ] [ Ethics ] [ Feedback ] [ Updates ] © Copyright 2000-, Climb-Utah.com |